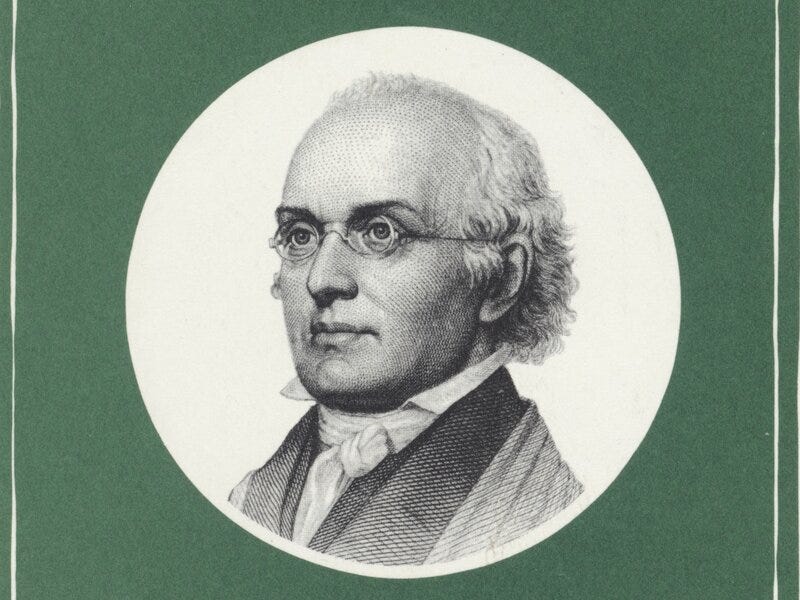

Joseph Story is not a name well-known among the American masses, but perhaps it should be. Nominated to the position by James Madison, Story served as associate justice on the Supreme Court from 1812 through 1845, an appointment that began not long after the founding of the country and during which many of the founding fathers were not only still alive, but still served in government. Story is well-known in many legal circles, as one of the foremost constitutional scholars. Middle Tennessee State University, for instance, has a web page that states Story “was one of the most renowned constitutional scholars in American history and arguably the greatest scholar ever to serve on the Supreme Court.” That is quite a laudation.

One of Story’s notable accomplishments was writing his quite lengthy Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (an electronic copy can be found here). This work, published in three volumes, is a treatise on the constitution intended for consumption by legal minds, including within many references to cases that had previously been tried as well as to writings by the founding fathers and other pertinent works. In order, however, to reach the masses, Story penned another more concise volume titled A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution. This text, written on a level for the ordinary citizen, was an expansion of another he wrote titled The Constitutional Class Book: Being a Brief Exposition of the Constitution of the United States intended for use (as the title implies) as a school textbook. Frankly, this book should be required reading in all high school civics or government classes.

Within the pages of this shorter tome, Story wrote the following paragraph regarding the election of Presidents:

§266. There probably is no part of the plan of the framers of the Constitution, which, practically speaking, has so little realized the expectations of its friends, as that which regards the choice of President. They undoubtedly intended, that the Electors should be left free to make the choice according to their own judgement of the relative merits and qualifications of the candidates for this high office; and that they should be under no pledge to any popular favorite, and should be guided by no sectional influences. In both respects, the event has disappointed all these expectations. The Electors are now almost universally pledged to support a particular candidate, before they receive their own appointment; and they do little more than register the previous decrees, made by public and private meetings of the citizens of their own State. The President is in no just sense the unbiased choice of the people, or of the States. He is commonly the representative of a party, and not of the Union; and the danger, therefore is, that the office may hereafter be filled by those, who will gratify the private resentments, or prejudices, or selfish objects of their particular partisans, rather than by those, who will study to fulfill the high destiny contemplated by the Constitution, and be the impartial patrons, supporters, and friends of the great interests of the whole country.

A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution

Imagine, this expanded piece was published in 1840 (the “Class Book” was published in 1834) and already the process for electing the president of the United States had been corrupted. How deeply corrupted the process had become at that time I cannot say. Looking now, however, at the current state of our Republic, the prophetic nature of Story’s writing is clear. We have reached a time when, not only is the President no longer “the unbiased choice of the people, or of the States,” but he is now hyperpartisan. Am I exaggerating? I think not.

Everything Story wrote here about the presidency, being “representative of a party, and not of the Union” (emphasis mine), being one “who will gratify the private resentments, or prejudices, or selfish objects of their particular partisans,” is such an incredibly accurate depiction of what we see happening today, that if it was not happening in his time, we would liken him to Elijah or Nostradamus.

Herein, Story also makes a very poignant observation about the constitutional vision for those in government, to “be the impartial patrons, supporters, and friends of the great interests of the whole country.” This is clearly no longer the case. Party politics have supplanted Constitutional conduct, and tribalism stands in place of truth. Our founding fathers, who were far wiser, despite their youth, than those now serving (if you can call it “serving”) in our government, espoused particular guiding principles that they expected would continue in their absence. Partisanship was not among those principles. As a matter of fact, the founding fathers believed the idea of political parties to be accursed due to the problems that follow factionalism. You can read some of their laments about political parties here: Who doesn’t love a party? This is, in part, why they created a Republic rather than a Democracy.

We must put partisan politics aside. If America is ever to “fulfill the high destiny contemplated by the Constitution,” people must begin to see beyond party to principles, and those principles must be the ones embraced by our founding fathers. Politicians today attempt to sell us on their principles, principles that may sound good, that may appear fair, or equitable, or even righteous. We must not be deceived, and we must not let party take preference over policy.

Perhaps Story wasn’t a prophet. He was considering his contemporaries when he penned this bit of perceptive wisdom. Yet his words ring true so very many years later. Our situation is not unique, but we are uniquely positioned to make a change before it is too late to recover. This Union belongs to the people, not any political party. It’s time the people return to the Republic’s founding principles and take their country back.