What do epidemiologists and meteorologists have in common?

They are both well-paid and manage to remain employed no matter how often they are wrong

We’ve all fallen victim at one time or another, probably many times, to a faulty weather forecast. It’s much more rare that a meteorologist gets a weather forecast right than wrong. Epidemiologists are the “weather reporters” of the health industry. Like meteorologists, it seems that epidemiologists have a knack for being incorrect.

If you’ve read my article on Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Medicine’s course “Covid Vaccine Ambassador: How to Talk to Parents,”

then you know that it was the second of their courses that I’ve taken through Coursera because they continue to send emails offering new courses.

The latest adventure on which I’ve embarked is a course to which Coursera invited me titled, “Infectious Disease Transmission Models for Decision-Makers.” This course explains how epidemiologists use modeling to try to predict the course of outbreaks of communicable pathogens. Just as meteorologists use mathematical models in an attempt to discern the upcoming temperatures, precipitation patterns, and major storms, epidemiologists use mathematical models in an attempt to foresee how a disease might spread among a population.

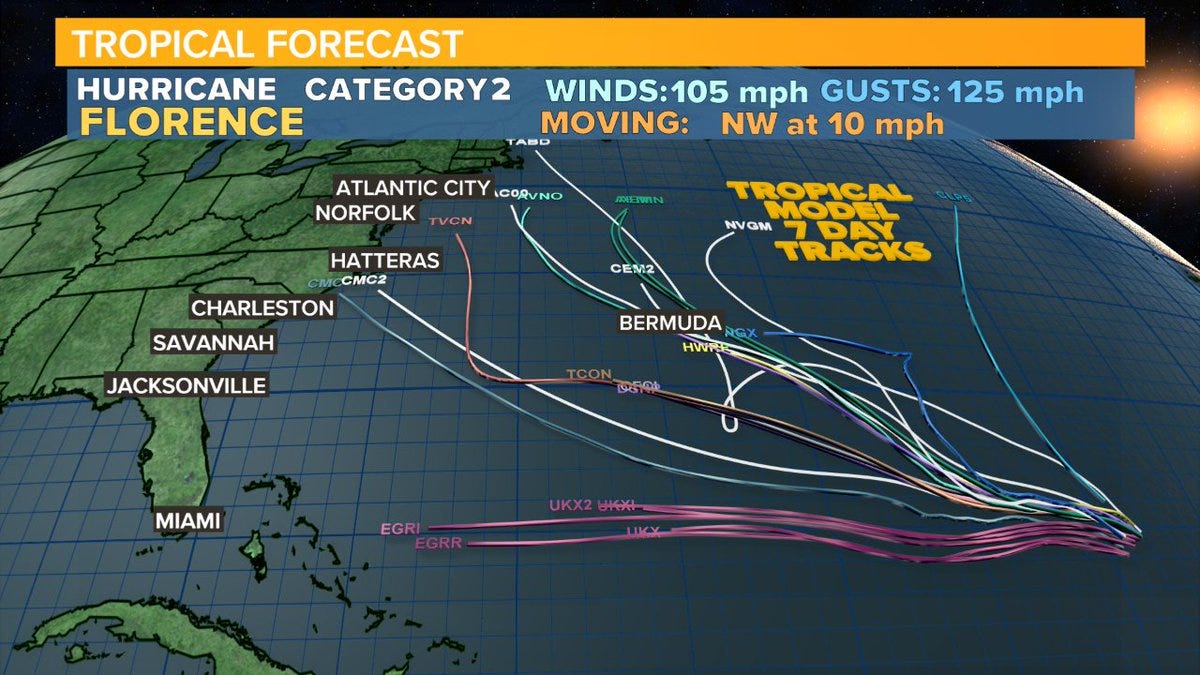

In weather forecasting, models use information such as atmospheric pressure, air currents, temperatures, etc. to try to predict what future temperatures, winds, and precipitation may be. In larger cases, attempts are made to predict the path a large storm, such as a hurricane, will follow, changes in the strength of the storm as it traverses the projected path, expected amounts of rainfall, and effects on tides. Anyone living in a coastal area of the US (and even some inland) are familiar with images like this:

In the same way, epidemiologists use models to predict the spread of infectious diseases, attempting to estimate how rapidly the disease will spread, the number of cases that will occur, impact on hospitals, number of fatalities, and other aspects of an outbreak. Inputs used for the most basic of epidemiological models are details such as percentage of the population susceptible to a pathogen, basic reproductive number (also known as R0 or R-naught), number of people who are infectious, and number of people who have recovered. There are several types of models that can be used, and each relies on different inputs and mathematical formulas.

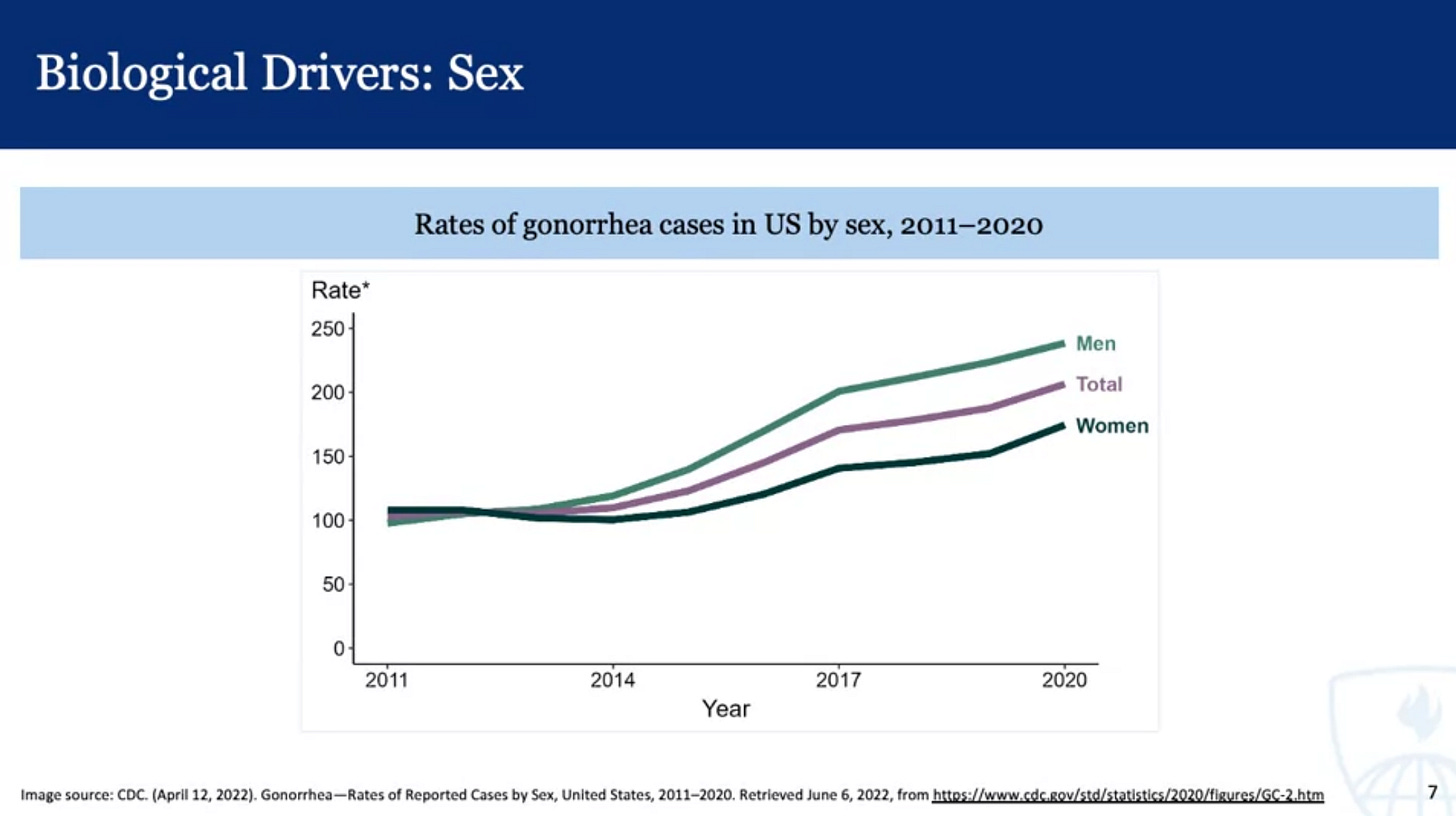

One of the problems, as the course readily admits is that all models include uncertainty in both the model structure and the parameters. This holds true for meteorology as well, though epidemiology has far more variables to take into consideration. As I learned early on in working with computers was the acronym GIGO - it stands for garbage in, garbage out. The best of systems will produce poor output if they are fed faulty data. This goes for modeling as well, whether certain aspects of transmission are neglected by a model or incomplete or erroneous data is fed to the model. For instance, drivers for the spread of a pathogen may include biological, behavioral, and ecological factors. What happens if a model is mistaken when considering these factors? Look at the following graph:

According to the course, the fact that rates of reported cases of gonorrhea is higher among men than women is a biological driver, in other words, there is something about male physiology that makes them more susceptible to gonorrhea than women. What if, however, the difference is actually due to behavioral drivers? Is it not more likely that men incur a higher rate of gonorrhea because they are more apt to sleep around or to do so more than women? Something this graph also doesn’t capture is that gonorrhea is more prevalent among homosexual men than heterosexual men - another behavioral factor. What about the consideration that men are more likely to seek out prostitutes who would have a high possibility of being infected and apt to pass that infection on? There are other factors this graph neglects, so it is a pretty poor example and certainly mischaracterizes the risk.

What if a pathogen is new? What if modes of transmission are not fully understood? With COVID-19, the original story was that it was not transmitted from one person to another, then we were told that it was transmitted by respiratory droplets, then it could be transmitted by contact with inanimate objects (fomite transmission), then fomite transmission was ruled out, then it could be spread by respiratory aerosols… Understanding of the mode of transmission of the virus was constantly in flux. Nevertheless, models were used to try to figure out how the disease would spread.

You may recall seeing graphs such as this:

A graph like this is more scary than watching Friday the 13th in a haunted house on halloween night! The problem is, the inputs for the graph are inaccurate, and there are too many variables that it cannot possibly take into account, yet models like this drove government interventions in their attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Some of the first models used came out of Imperial College in London. These models were produced by Neil Ferguson and his team. Neil Ferguson has an interesting history of epidemiological predictions. In 2001, Ferguson predicted that up to 150,000 people could die from an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among cattle and sheep; less than 200 people died. In 2002, he predicted that up to 50,000 people would likely die from an outbreak of mad cow disease in the U.K.; there were only 177 related fatalities. In 2005, Ferguson predicted that up to 150 million people could die from pandemic avian flu; between 2003 and 2009, a worldwide total of 282 were killed by the virus. In 2009, worst case estimates of potential British deaths from H1N1 flu based on Fergusons work were numbered at 65,000; 457 people in the U.K. met their demise as a result of this swine flu. Then, in 2020, along came COVID-19. Ferguson and his team predicted up to 2.2 million U.S. deaths; the deaths approached nowhere near this number, and evidence is yet being uncovered showing that many deaths attributed to COVID-19 since the beginning of the outbreak were not actually caused by the virus. Had he been a prophet in Old Testament times, Ferguson would have been stoned to death.

Is his accuracy surprising though? Weather reporters, whose forecasts rely on far fewer variables, are incredibly inaccurate. A meteorologist has the same probability of accurately predicting the weather seven days from now as he or she would predicting the lottery numbers; the chances of an epidemiologist accurately predicting the spread of a disease are far slimmer.

“But this is just modeling,” you may say. “No one expects perfection.” Perhaps, but this becomes very problematic when policy decisions are made based upon these prognostications.

Consider, if a hurricane model predicts landfall of a major storm, and local government reacts by issuing a “mandatory” evacuation, what is the damage if the model is wrong? First, let me state that I don’t believe there should be such thing as a “mandatory evacuation.” Should people decide to risk riding out a major storm and losing their lives, it is not a governmental issue. The US Constitution and most state constitutions protect people from being derived of their liberty and property apart from due course of law. Since living and staying on one’s own property does not violate any law, no one should be forced to leave, even when danger is imminent. Part of living in a free society involves daily gauging and accepting certain amounts of risk. That said, if the government issues a call for evacuation, and the model proves wrong because hurricane turns aside or dies off and does not make landfall where expected, what is the resulting detriment to the residents who leave their homes? Perhaps they are inconvenienced for a couple of days, maybe miss a couple of days work (which could be fairly detrimental for some), and then return home unharmed.

Now, consider if an epidemiological model predicts the rapid spread of a pathogen and countless deaths that will follow. Imagine the government reacts by shutting down businesses, forcing people to stay home, wear masks, even take experimental injections. Picture, if you will, these models predicting hospitals being overrun, and therefore turning away patients suffering other ailments in order to make sure there is room for those infected. Contemplate the cost of setting up temporary emergency hospitals to handle the overflow of infected patients. Surely this all sounds familiar.

I don’t need to recount all that was enacted in order to “flatten the curve” here in the U.S., suffice to say the nation is still reeling from the measures enacted and the billions of dollars spent to fight the evil virus. The economic and social impacts foisted upon Americans are immeasurable. Businesses that people spent a lifetime building, and into which they poured their hearts and souls, shuttered permanently. Millions of jobs were lost. Supply chains were disrupted. People struggled not only financially, but psychologically, to cope with what was happening around them. Millions were pushed, almost forced into receiving an experimental pharmaceutical that had not even completed phase 3 clinical trials (the current President did attempt, via OSHA, to mandate the COVID shots; and for more information on it being experimental, ineffective, and not having completed trials, see the paper I wrote about the COVID jab here:

). In short, our booming economy was devastated, record-high employment was destroyed, and people’s lives were left in disarray. Perhaps most poignantly, the government seized and exercised powers never before seen in the history of this country, and this is a serious problem.

Our elected officials, in declaring an “emergency,” laid claim to powers not granted them in the U.S. Constitution nor in state constitutions. Just as I mentioned above with extreme weather events, such emergencies do not suddenly grant the government additional authority. It is not the government’s job to mitigate our risk of disease - an individual’s health is, in general, not the government’s business at all. Nowhere does the Constitution bestow upon the government the responsibility of watching over people’s health. As stated earlier, gauging risk and deciding how much to accept is the purview of the individual. The government’s job is to protect the individual’s liberty to do so. As long as we continue to allow the government to use such emergencies to infringe on the liberties they were established to protect, our rights will gradually diminish. New crises will arise for which government will declare powers to presumably assuage. All the while, our freedom is chipped away little by little. All this because of a model, and because those who believed the model fomented fear.

While models can, to some degree, be useful to help citizens make informed decisions for themselves, they should not be used for informing government policy, especially when a model has as much chance of correctly divining the course of a viral outbreak as does a reading you’d get by calling 1-800-PSYCHIC.

One of the things I enjoy/like about your articles is that they have an "academic" feel to them. Your points are backed by well researched information. You state YOUR perspective on the issue without a doubt. But you also leave it up to the reader to decide for themselves what to do with the information that you present.

That being said, I tend to agree with you on a vast majority of your opinions on any given topic so you are basically preaching to the choir where I am concerned. 😄

Growing up on the east coast in Charleston, SC I learned how to gauge the storm tracks with the help and lessons from my grandfather. He was no expert of any kind on the subject, he was just an intelligent man that knew how to add 2 and 2 to get 4. He did pretty darn good where it came to predictions on landfall. But the information he was getting from the newspaper and TV had to be up to date and accurate in order for HIM to be accurate.

I guess that is the point of the article. If the information given to people to make INTELLIGENT and INFORMED decisions is flawed to begin with then those decisions are going to have serious negative impacts.

Your analogy of mandatory evacuation reminds me of when hurricane Hugo tore through the Lowcountry. The peninsula of Charleston was a "MANDATORY" evacuation. The residents were told that IF they chose to stay they would NOT be able to get ANY emergency assistance until well after the storm was over. (Giving them the option of taking their lives in their own hands)

I also remember police chief Ruben Greenberg doing an emergency simulcast and letting EVERYBODY know that ANYBODY caught looting during or after the storm would BE SHOT ON SIGHT. He understood that forcing people out of their homes opens them up to the possibility of theft by the scummier elements of society.